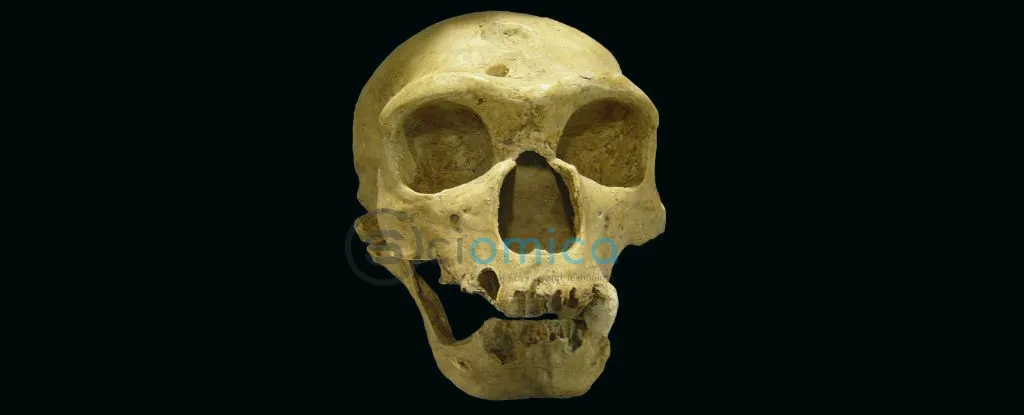

Recent research from the University of Michigan has reignited the long-standing debate over the extinction of Neanderthals, suggesting that cosmic and environmental factors may have played a key role in their demise. The study, published in the journal Science Advances, proposes that a significant shift in the Earth’s magnetic poles around 41,000 years ago, known as the Laschamp event, may have created conditions that were unsustainable for Neanderthals.

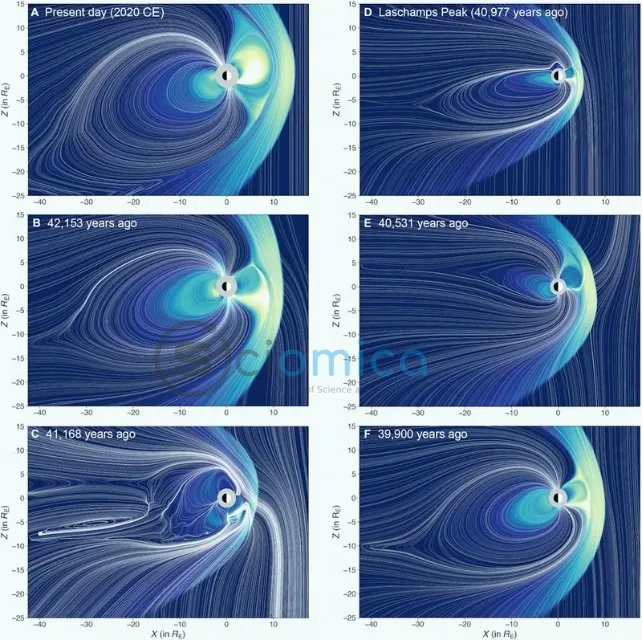

Lead researcher Agnit Mukhopadhyay, a space physics expert, indicated that the weakening of Earth’s magnetic field during the Laschamp event led to increased exposure to cosmic and ultraviolet radiation. This, according to Mukhopadhyay, may have made the environment hostile enough to give an evolutionary edge to Homo sapiens over their Neanderthal counterparts.

In this scenario, Homo sapiens may have benefitted from wearing close-fitting clothing and using ochre, a mineral believed to provide some protection against solar radiation, while also seeking refuge in caves to shelter from the harsh environmental conditions. This advantage may have facilitated the survival of our ancestors while Neanderthals struggled.

Clothing and Technological Advantages

The hypothesis suggests Neanderthals lacked access to tailored clothing that could protect them from the elements. Although evidence of sewing needles has not been definitively linked to Neanderthals, recent archaeological finds indicate that Neanderthals utilized tools for hide processing, which might have allowed them to create garments despite not having needles as we understand them today.

The study argues that while ochre was used for protection against UV rays, its use was not exclusive to Homo sapiens. Neanderthals also utilized ochre, evidenced by archaeological discoveries of ochre pigments in Neanderthal sites indicating a long-standing relationship with this mineral.

Population Dynamics and Adaptability

Another critical aspect to consider is the population dynamics of the time. Special attention is drawn to the possibility that Neanderthals, being fewer in number, could have been absorbed into larger Homo sapiens groups rather than experiencing a complete extinction. This assimilation is evident in the genetic makeup of modern humans, which reflects interbreeding between the species.

However, Mukhopadhyay’s simplistic attribution of Neanderthal extinction to their failure to adapt to increased solar radiation overlooks the variety of complex factors contributing to their decline. Researchers argue that the archaeological record does not support a direct link between the Laschamp event and Neanderthal extinction, as no drastic demographic shifts align with the magnetic event. Moreover, if radiation exposure were a decisive factor, similar patterns of mortality would likely be observed in various human populations, which is not the case.

In conclusion, while the interplay between environmental factors and human evolution is critical, the simplistic narrative of Neanderthals as victims of their circumstances omits the complex cultural and technological landscape in which they thrived for over 300,000 years. Answers regarding their fate will require a more nuanced approach that encompasses a wealth of archaeological, genetic, and anthropological evidence.