The concept of the Anthropocene— a term used to describe the era in which human activity has had a profound impact on Earth’s climate and ecosystems—continues to spark debate among scientists. Recent studies suggest that human-induced changes to the environment may date back to 1592, slightly earlier than the dates widely proposed by previous research.

For at least 10,000 years, humans have altered their surroundings, but the significance of the Anthropocene lies in its acknowledgment of the extensive and lasting influence humanity has had globally. Although the term has not been formally recognized as a geological epoch, many scientists consider it a valuable descriptor of this era of environmental change repurposed through human activity.

Scholars have argued for various start dates of the Anthropocene—from the early 17th century to the mid-20th century when the detonation of atomic weapons altered the atmosphere significantly. However, a recent study by Vincent Gauci, a Professorial Fellow at the University of Birmingham, argues for an earlier beginning of 1592, coinciding with the European arrival in the Americas.

The research builds on previous work by Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, who proposed 1610 as a starting point based on an unprecedented decline in atmospheric CO₂ linked to forest regrowth following European colonization. Their hypothesis cites the “Orbis spike,” an event marked by falling CO₂ levels as millions of hectares of farmland were left unattended due to massive demographics shifts caused by European diseases such as smallpox.

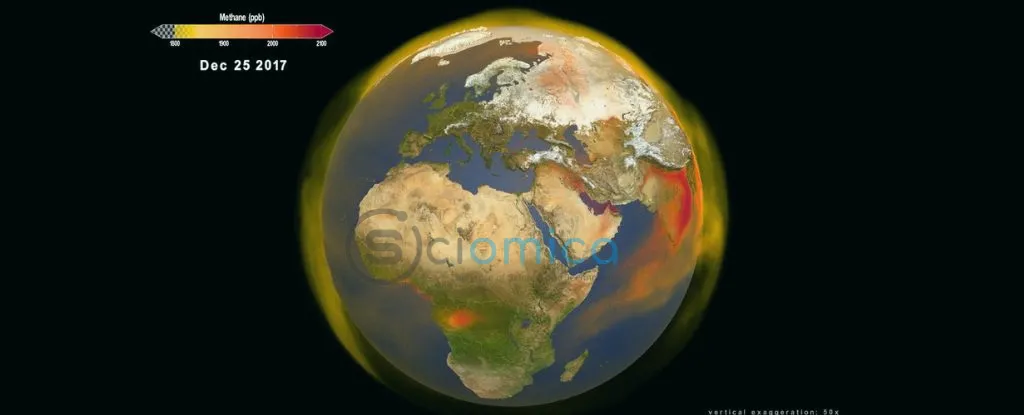

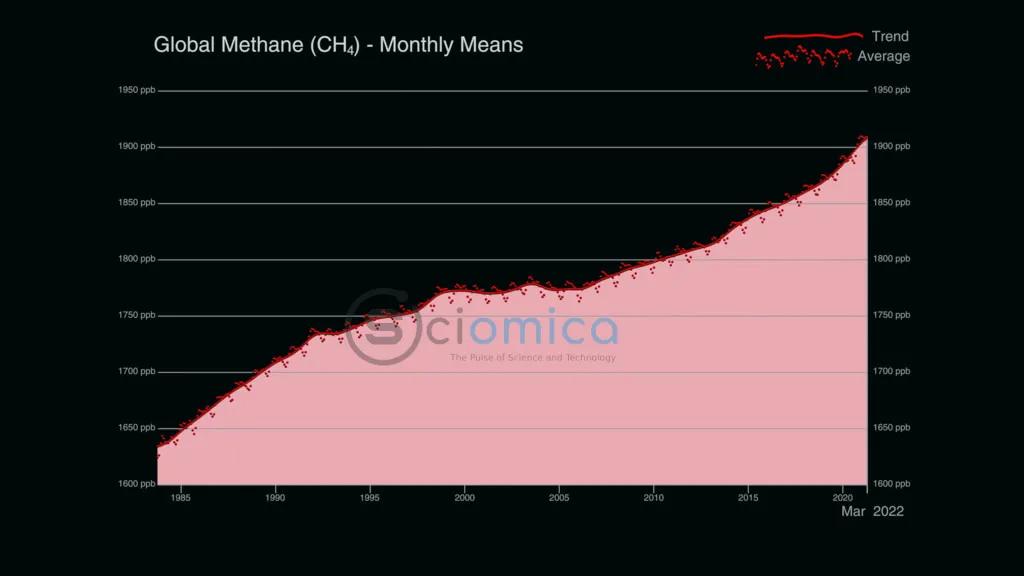

Gauci’s findings indicate that the reduction in methane levels recorded in Antarctic ice cores aligns with the arrival of Christopher Columbus and subsequent changes to the environment, suggesting that methane concentrations in 1592 were at a historic low. His research underscores that trees play a crucial role in the carbon cycle, both as sources and sinks of methane. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, about 80 times more impactful than carbon dioxide over a two-decade period.

Trees as Methane Sinks

The study highlights how trees and their bark surfaces serve as crucial interfaces for methane exchange. Research reveals that trees, particularly in swampy or floodplain areas, significantly affect methane emissions and absorption. Gauci argues that the increase of tree coverage on abandoned farmlands allowed for more surface area to absorb methane, contributing to the atmospheric decline observed in the late 16th century.

Further, the relationship between forests and rainfall may have facilitated this reduction in methane levels. The trees’ ability to intercept rainfall could limit the amount of water flowing into wetlands—noteable sources of atmospheric methane—resulting in lowered overall atmospheric concentrations of this greenhouse gas.

While discussions continue over the Anthropocene’s official start, Gauci’s research illustrates profound human influence on earth’s ecological systems, suggesting an intricate, evolving connection between humanity and nature that stretches back centuries.

As scientists and researchers delve deeper into understanding these dynamics, the narrative surrounding humanity’s impact on the environment is likely to expand and evolve, reshaping our knowledge of history and its implications for the future.

Vincent Gauci, Professorial Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham