In the realm of science, few topics spark as much intrigue and debate as the nature of the human mind. Recently, physicist Sabine Hossenfelder made waves with her bold claim that free will is an illusion and that humans are merely “big bags of particles” governed by the deterministic or random laws of physics. Her assertions, rooted in a materialist view of the universe, suggest that the human brain operates like a machine, fully explicable by physical processes and potentially replicable by a computer. Yet, this perspective raises profound questions about consciousness, free will, and the essence of what makes us human—questions that some argue physics alone cannot answer.

Hossenfelder’s argument hinges on the idea that everything in the universe, including the human mind, can be reduced to physical processes. She posits that the brain’s functions, from thoughts to emotions, are the result of particle interactions governed by natural laws. In her view, there’s nothing inherently special about the brain that a sufficiently advanced computer couldn’t simulate. Consciousness, love, and even existential dread are, in this framework, mere electrochemical states—complex, perhaps, but ultimately material. This perspective aligns with 18th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who championed a materialist philosophy that reduced human experience to physical causes and effects.

However, this reductionist view faces significant challenges. Critics argue that equating the mind to a machine overlooks the subjective nature of human experience. While neuroscience can map brain activity associated with seeing the color red or feeling joy, it cannot capture the lived experience of those sensations. This gap is famously illustrated by philosopher Frank Jackson’s “Mary’s Room” thought experiment. In it, Mary, a scientist who knows everything about the physics of color, has never seen red herself. If she finally experiences it, does she gain new knowledge? Most would argue yes, suggesting that subjective experience transcends mere data—a challenge for Hossenfelder’s claim that a computer could fully replicate the human mind.

The debate extends to the concept of free will. Hossenfelder asserts that because physical laws are either deterministic or random, humans cannot have true control over their actions. This view dismisses free will as an illusion, a byproduct of brain processes that follow predictable or probabilistic patterns. Yet, alternative philosophical perspectives offer a counterpoint. Compatibilism, for instance, suggests that free will can coexist with determinism. It argues that while our choices may be shaped by circumstances—our memories, emotions, or environment—we can still act according to our desires, giving a sense of agency. This idea, traced back to 16th-century theologian Luis de Molina, posits that in different hypothetical scenarios, a person might choose differently based on varying inputs, thus preserving a form of free will.

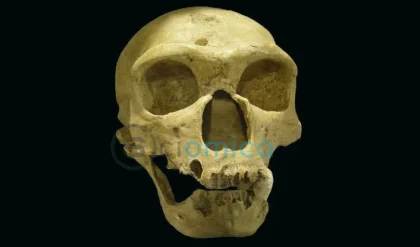

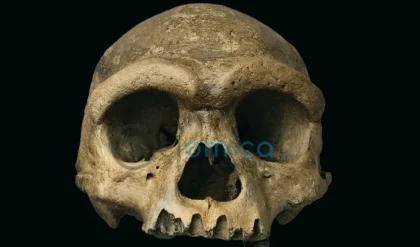

Another perspective, dualism, proposes that the mind is distinct from the body, a view rooted in the philosophies of Plato and Descartes. A weaker form, inspired by St. Thomas Aquinas, suggests that while mental states are tied to the brain, consciousness itself may be an immaterial phenomenon, embodied yet not fully reducible to physical processes. Alternatively, panpsychism posits that consciousness is a fundamental property of all matter, potentially explaining how even a machine might possess awareness if constructed correctly. These theories highlight the complexity of consciousness, a phenomenon that remains one of science’s greatest mysteries.

Hossenfelder’s dismissal of anything beyond the material rests on the claim that there’s no evidence for non-physical aspects of the mind. Yet, this assertion is not without flaws. Concepts like truth, logic, and morality—central to human cognition—are inherently immaterial. The statement “1+1=2” holds true regardless of physical context, and moral judgments, like deeming an action right or wrong, cannot be fully explained as evolutionary adaptations. Even the notion of “evidence” itself is an abstract, non-physical concept, undermining the strict materialist stance. By assuming everything must be material, Hossenfelder risks falling into scientism, the belief that science alone can explain all aspects of reality.

The implications of this debate extend far beyond academic circles. For the average person, free will is less about cosmic laws and more about everyday choices—whether to trust a friend, pursue a career, or resist coercion. These decisions feel deeply personal, shaped by a mix of internal desires and external pressures. Philosophy and theology, unlike physics, offer tools to examine these choices critically, encouraging individuals to question their assumptions and live more intentionally.

While physics provides invaluable insights into the mechanics of the universe, it may fall short in capturing the full scope of human experience. The mind, with its capacity for love, creativity, and self-reflection, challenges the notion that we are merely machines. As neuroscience and philosophy continue to explore these mysteries, one thing is clear: the question of what makes us human is far from settled. Whether through compatibilism, dualism, or panpsychism, the search for answers pushes us to look beyond particles and into the essence of consciousness itself.