As a child, the allure of reports and documentaries showcasing field research captivated my imagination. I often pondered the experiences of researchers and the knowledge they produced. My journey as an ecologist led me to seek methods that deeply connect scientific inquiries with their real-world contexts. This perspective opened my eyes to the importance of understanding humans as integral components of ecological systems, rather than viewing them as separate from nature. Consequently, I began to explore integrative research methods that incorporate local and traditional knowledge, with the goal of making scientific research more relevant and accessible to the communities involved.

Currently, my research is centered around ethnobiology, which is an interdisciplinary field that intersects ecology, conservation, and traditional knowledge. This area of study allows us to investigate not just the biodiversity within a particular region, but also the intricate relationships that local communities maintain with their surrounding species. By understanding these dynamics, we can identify critical areas that necessitate focused conservation efforts. Those who have called a place home for generations often possess an unparalleled understanding of its nuances, allowing for the early detection of environmental changes. Collaborative projects with community members foster engagement, as they recognize their roles as active participants in the research process. This collective involvement is fundamental to successful conservation efforts.

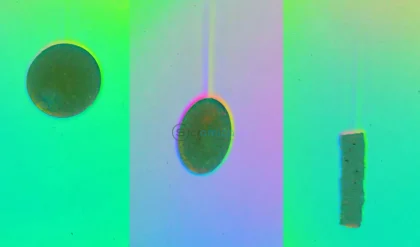

One of the most compelling legends related to our research is that of the Great Snake—an enormous serpent said to dwell beneath the Amazon River and slumber under the town. Local residents describe this creature, believed to be an anaconda, as capable of shaking the river’s waters with its immense movements and possessing fiery eyes during the night. Folklore suggests that these snakes can grow large enough to consume substantial animals, including humans.

Interestingly, the perception of anacondas as mythological entities is shifting. While the mythology certainly persists, there are practical concerns regarding the loss of poultry, particularly chickens. Many community members now view anacondas through an economic lens, identifying them as stealthy thieves rather than spiritual beings. A recurring sentiment among locals is that anacondas target their chickens, as one resident mused, “If one clucks, she comes.” This conflict is often framed in terms of financial loss, especially since raising chickens is not only an investment of time and resources but also involves the cost of feeding them.

In discussions, various residents articulated their frustrations over losses incurred due to anacondas: “The biggest loss is that they keep taking chicks and chickens.” These sentiments reflect a deep-seated concern, particularly when residents share stories of needing to fortify their chicken coops to deter incursions by these snakes.

Despite ethnobiology being a well-established field, it often faces skepticism regarding its scientific rigor. Critics question its findings, particularly when they rely more on qualitative data than on hard statistics. However, it’s essential to understand that this discipline adheres to rigorous methodologies, relying on carefully gathered data, cultural insights, and the traditional knowledge of local peoples.

Looking ahead, I envision increased focus on conservation projects that empower local communities. Incorporating their voices and traditional knowledge can lead not only to more effective conservation strategies but also to equitable solutions that respect their rights and needs. Embracing open science principles can significantly amplify the reach of research findings, fostering collaboration across scientific and community contexts and ensuring that valuable insights translate into meaningful action for both conservation and sustainability.

Reference:

- Beatriz Nunes Cosendey, Juarez Carlos Brito Pezzuti. The myth of the serpent: from the Great Snake to the henhouse. Frontiers in Amphibian and Reptile Science, 2025; 3 DOI: 10.3389/famrs.2025.1567889